Why the Preface, Agnus Dei, and Pax Domini?

Real Presence

By T. R. Halvorson

NOTE: This article may be downloaded as a PDF Document

The Service of the Sacrament begins with the Preface.

Why?

Is it just because we need some way of beginning? Is it because prefaces are how most things are begun? Is it a smoothening filler to glue the Service of the Sacrament together with the Service of the Word? Is it just a nice way to shift gears?

“The Preface is one of the oldest parts of the liturgy, and could have been used by the apostles.”[1] It “is almost universally used in both East and West,”[2] It is “the oldest and least changed part of the liturgy.”[3] So it does not seem likely that we do this just because we have to start somewhere.

As soon as the Words of Institution are said or sung and Pax Domini (Peace of the Lord) is proclaimed, immediately we sing Agnus Dei (Lamb of God).

Why?

Is it just because we need something to do while the pastor and his assistant are communed? For those who practice fraction (breaking the bread), do we sing Agnus Dei just to cover the time fraction takes? Historically, some churches did keep singing it over and again until the fraction was done.[4]

I say “we” sing Agnus Dei meaning the church since 700 A.D. and Lutherans still today. But not everyone does. Others see no reason for it. The Second [Anglican] Prayer Book omitted it in 1552. A proposal to restore it to the English Book in 1661 failed. A similar effort in 1928 was defeated.[5]

Why?

Real Presence.

The Papists had clouded the Sacrament with sacrifice by a sacerdotal priesthood, withholding of the Words of Institution from the people by whispering them and withholding one of the elements from the people. All that fit the error of transubstantiation. It all had the effect of reducing or removing the presence of Christ from the people.

On the other side, in their reaction against the Papist errors, the Radical Reformation, Enthusiasts, Anabaptists, Calvinists, and the Reformed denied Real Presence. Where the Papists made Communion into a work of the priests, the non-Lutheran Reformation made it into a work of the people by their faith and their grasping for spiritualist remembrances. According to them, it is your faith that makes the bread the spiritual body of Christ. It depends on you. This mystical labor keeps pressing toward an every-receding mirage of the presence of Christ. By a different means, this accomplished the same thing as the Papist errors: reducing or removing the presence of Christ from the people.

Luther reformed the Mass. He uncluttered the Sacrament from both kinds of human-effort sacrifices (sacrifices of the priests and sacrifices of the people).[6] He emphasized Christ’s Words of Institution and taught that the Words mean what they plainly say. “This is my body, which is given for you.” “This cup is the new testament in my blood, which is shed for you for the forgiveness of sins.”

According to the Lutheran confessions, nothing depends on you.[7] There is no labor here for you. Instead, Jesus by his Word makes bread his body and wine his blood and makes them a gift to you: “take,” “eat”, “drink,” and “given.” By his Word, the bodily presence of Christ is real regardless whether the priest is righteous, regardless whether the communicant is sincere or a hypocrite, and regardless of faith or feelings. Christ’s Word does what it says.

Having decluttered the Mass, centered it on the Words of Institution, and restored Real Presence against transubstantiation on one side and mysticism on the other, now we have a pure Service of the Sacrament.

In the Preface, Real Presence is why the service begins with, “The Lord be with you.” What is this? The words plainly speak of the presence of the Lord. “With” means presence. The words call forth childlike faith that simply believes “This is my body.”

The Greeting claims and proclaims the presence of the risen Lord as the liturgist in the thanksgiving and sacramental celebration (Luke 1:28; 2 Thess 3:16; 2 Tim 4:22)[8]

The Lord being sacramentally present with us is what the Sacrament is about. Clear the clutter. Hear the Preface. “The Lord be with you.” Anticipate the Words of Institution. Believe again, “This is my body, which is given for you” and “This cup is the new testament in my blood, which is shed for you for the forgiveness of sins.”

The pastor prays this for us, and then we pray it for him, either “And with thy spirit,” or “And also with you.”

This is the timeless worship of all the saints including the departed who are “present with the Lord.” (2 Corinthians 5:8) So the Preface continues, “Lift up your hearts.” “We lift them up onto the Lord” In simplicity, we understand Communion with “the holy Christian church,” as we confess in the Creed. The whole church worships in the presence of the Lord.

The Preface is foreshadowed by Boaz. “Now behold, Boaz came from Bethlehem, and said to the reapers, ‘The Lord be with you!’ And they answered him, ‘The Lord bless you!’” (Ruth 2:4). Boaz, as kinsman redeemer of his bride, Ruth, foreshadows Christ the kinsman redeemer of his Bride, the Church. He comes from Bethlehem, the house of bread (beth, house and lehem, bread.) He comes to the reapers who reap the bread of life and says, “The Lord be with you.” The reapers answer, “The Lord bless you.” Like Boaz coming from house of bread, the pastor comes from the altar of bread to us reapers of the bread of life and says, “The Lord be with you.”

The Words of Institution and the reception of bread and wine happen so fast we could miss Real Presence. The Preface helps us. It says, hear the Word when it is spoken.

123. What is its purpose?

To greet the worshipers with a blessing; to invite attention; to incite devotion; and to suggest the coming act of worship.[9]

Stated another way, “The presider and the congregation committed to his care prepare themselves for the consecration.”[10]

When does the consecration happen? Paul says, “The cup of blessing which we bless, is it not the communion of the blood of Christ?” (1 Corinthians 10:16) Notice, “which we bless.” We bless the cup when the pastor says the Words of Institution. Then the cup is “the communion of the blood of Christ.”

When you are at the Communion rail and see the cup coming your way, you are seeing Christ coming toward you. You are seeing with his blood what He shed it for, the forgiveness of your sins, coming your way.

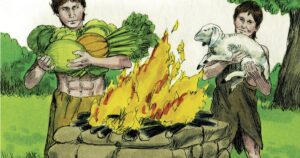

When John saw Jesus coming toward him, when he saw the forgiveness of sins coming his way, what happened? “The next day John saw Jesus coming toward him, and said, ‘Behold! The Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world!’” (John 1:29) So when we hear the Words of Institution and the distribution begins, we join John.

O Christ, Thou Lamb of God, that takest away the sin of the world, have mercy upon us.

O Christ, Thou Lamb of God, that takest away the sin of the world, have mercy upon us.

O Christ, Thou Lamb of God, that takest away the sin of the world, grant us Thy peace.

Amen

John had the real presence of Jesus and so do we. Agnus Dei hears the Word, “This is my body.” Agnus Dei believes the Word, “This is my blood” and “Shed for you for the forgiveness of sins.” “It acknowledges the real presence of Christ with his sacrificed body and blood and asks for his peace.”[11]

Certainly not just eating and drinking do these things, but the words written here: “Given and shed for you for the forgiveness of sins.” These words, along with the bodily eating and drinking, are the main thing in the Sacrament. Whoever believes these words has exactly what they say: “forgiveness of sins.” (Small Catechism, Baptism, Question 4)

Agnus Dei sees coming toward us what John saw. The Word of Christ makes it so, and nothing depends on the pastor or you.

Perhaps [Agnus Dei] was introduced into the liturgy because there were questions about Christ’s real presence, for the Agnus Dei states in unequivocal terms that what is present on the altar is none other than the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world.[12]

Now we can understand why Agnus Dei did not survive in the Anglican liturgy. The Anglican Communion is a mixed bag with Papist, Lutheran, and Reformed influences. The split votes on things like Agnus Dei reveal the ratios.

The Agnus Dei serves as a hymn of adoration to the Savior Christ who is present for us in his body and blood. It is for this reason that the hymn did not survive in the liturgies of Reformed churches, which refused to affirm the real presence of the body and blood in the sacramental elements.[13]

We have seen that the Lutheran Church places the Preface and Agnus Dei in the Service of the Sacrament because of Real Presence. Now for a bonus item. The Church places the Pax Domini (peace of the Lord) between the Words of Institution and Agnus Dei for the same reason: Real Presence.

The Sacrament proclaims the Lord’s death until He comes. “For as often as you eat this bread and drink this cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death till He comes.” (1 Corinthians 11:26). When Jesus died and then came bodily to the disciples He said, “Peace be with you.”

Then, the same day at evening, being the first day of the week, when the doors were shut where the disciples were assembled, for fear of the Jews, Jesus came and stood in the midst, and said to them, “Peace be with you.” When He had said this, He showed them His hands and His side. Then the disciples were glad when they saw the Lord. (John 20:19-20)

He came. He stood. He showed his hands. He showed his side. This is real presence, bodily presence of the risen Christ. In the Sacrament we proclaim his death till he comes. We also proclaim that He comes back from the dead with Real Presence in the Sacrament. Of course we are not overlooking that proclaiming the Lord’s death until He comes refers to his future coming again to judge the living and the dead. But we are proclaiming that, sacramentally, He already does come bodily. We proclaim that the bread is his true body. Since he comes in this way after his death, we include the Pax Domini just after the Words of Institution that speak of his death in the giving of his body and the shedding of his blood. The pastor speaks the peace of the Lord to us as Christ spoke his peace to the disciples.

Luther lifted this brief blessing out of relative obscurity and gave it something more than its original dignity and significance as a blessing of the people, and, indeed, a form of absolution. In his Formula Missae (1523), he says: “It (the pax) is the voice of the gospel announcing the forgiveness of sins, the only and most worthy preparation for the Lord’s table.”[14]

Having heard the Words of Institution and the Pax Domini, then we confess what we have heard. We confess his presence and peace in Agnus Dei.

Real Presence — and the forgiveness and peace it brings — is the thread of the necklace on which all the pearls of the Service of the Sacrament are strung.

[1] Arthur A. Just, Jr., Heaven on Earth: The Gifts of Christ in the Divine Service (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2008), 211-212.

[2] Fred L. Precht, ed., Lutheran Worship: History and Practice (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1993), 420.

[3] Luther D. Reed, The Lutheran Liturgy (Philadelphia: Muhlenberg Press, 1947), 324.

[4] Reed, The Lutheran Liturgy, 370.

[5] Reed, The Lutheran Liturgy, 369-370.

[6] Bryan Spinks, Luther’s Liturgical Criteria and His Reform of the Canon of the Mass (Bramcote, Notts.: Grove, 1982).Carl F. Wisloff, The Gift of Communion: Luther’s Controversy with Rome on Eacharistic Sacrifice, trans. Joseph M. Shaw, pp. 167-168 (Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House 1964).

[7] James L. Brauer, ed., Worship, Gottesdienst, Cultus Dei: What the Lutheran Confessions Say About Worship (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2005), 131-163.

[8] John W. Kleinig, Course Notes for Liturgics (North Adelaide: Australian Lutheran College, 2009), 38.

[9] An Explanation of the Common Service, 5th ed. (Grand Rapids: Emmanuel Press, 2006), 51.

[10] Precht, Lutheran Worship, 420.

[11] John W. Kleinig, “Course Notes for Liturgics,” (North Adelaide: Australian Lutheran College, 2009), 46.

[12] Just, Heaven on Earth, 233.

[13] Precht, Lutheran Worship, 430.

[14] Reed, The Lutheran Liturgy, 366.