Note: This book review is distilled from a more extensive Commentary on Suffering, Not Power, by Benjamin Wheaton, available for download as a PDF here.

In Suffering, Not Power: Atonement in the Middle Ages, Benjamin Wheaton reexamines the popular claim by the Lutheran Gustaf Aulén that the Christus Victor idea of the atonement prevailed throughout the Middle Ages until Anselm’s focus on expiation and propitiation in Cur Deus Homo.

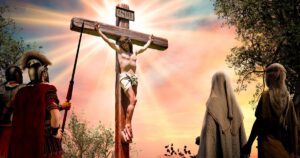

As taught by the church in the Middle Ages, was the atonement first a matter of Christ exercising power to defeat our cosmic enemies? Or, was it first a matter of the suffering and sacrifice of the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world, and then as an effect of God having dealt with our sin, we are released from captivity and bondage to death and the devil. How are penal substitution and vicarious satisfaction on the one hand and Christus Victor on the other hand, related?

Wheaton rightly begins by observing what Aulén himself said he was doing. “My aim in this book has been throughout an historical, not an apologetic aim.”[1] A. G. Herbert said in the translator’s preface to Aulén’s book: “This book is strictly an historical study; it contains no personal statement of belief or theory of the Atonement.”[2] Aulén was writing history, not dogmatics.

Wheaton’s MA is in Medieval Studies. His PhD is from the Centre for Medieval Studies at the University of Toronto. Wheaton’s study is also historical. In other words, we are not pitting a theological work against a historical study. We are challenging history in a historical study with another historical study of the same issue, this time by a historian of the era, not by a professor of systematic theology as Aulén was.

The Middle Ages were about 1,000 years. Europe is almost 4 million square miles. It had many countries, ethnicities, languages, cultures, classes, and genres of literature. Wheaton needed a strategy for sampling sources with a good chance of yielding a representative picture. Wheaton’s strategy spreads the sources he samples across the 1,000 years by selecting from the early, middle, and late Middle Ages; across the geography of Europe; across languages; across cultural contexts; across literary genres; across the diversity of purposes of the writings examined; across diverse types of authors; and across diverse intended audiences.

Besides that, Wheaton emphasizes the reception history of the authors to be sampled. The sources he examines, even if not generally familiar to today’s readers, have impressive and sometimes enormous reception history making them credible representations of the theology of the Middle Ages.

What does Wheaton find in his sampling? To be sure, Christus Victor features in the theology of the Middle Ages. Sometimes it is even portrayed in overwrought images. But it figures into the theology of atonement in a particular way. Christ’s victory over our enemies and his deliverance of us from the captivity and bondage to death and the devil are effects of Christ’s primary achievement: a sacrifice of expiation and propitiation made by God to God, thereby reconciling mankind to God and God to mankind.

Our guilt for sin was the basis of the devil being our jailor and death being our hangman as agents of God’s judgment. The vicarious satisfaction Christ rendered to God as our substitute dissolved the basis of sin and guilt that were the foundation of the devil’s power. The devil had no power or rights of his own. He had only a derived power, assigned to him by God, based on God using him to execute God’s judgment. With judgment removed by Christ and the delegation of power from God revoked, voila, deliverance from the devil. The deliverance is not by an exercise of power, but by justice having been met for us in the suffering and sacrificial life and death of Christ. In God’s mercy, as he imputed our sins to Christ, so He imputes Christ’s righteousness to us.

As the reader absorbs the evidence Wheaton presents for the standing and influence of his sources, it becomes difficult to defend Aulén’s having missed them. Aulén, however, though purporting to conduct historical research, was not a historian as Wheaton is. He was a bishop and professor systematic theology. By training, Wheaton is more suited to this type of work.

Wheaton modestly calls his book an “experiment.”[3] In my estimation he got well beyond a proof-of-concept. Unless he or someone else carries the method forward to a denser sampling of the corpus, Wheaton’s work in Suffering, Not Power should acquire and retain status as the standard in this area of historical theology in English. It ought to displace Aulén’s Christus Victor. Lutherans along with all other Christians will have more need and derive greater benefit from knowing Wheaton’s work than Aulén’s.

Given that Aulén was a systematic theologian, it is even more distressing that besides missing what the Middle Ages church taught about atonement, Aulén also missed how his idea conflicts with Luther’s explanation of the Second Article of the Creed in the Large Catechism, and conflicts with how vicarious satisfaction is confessed as the ground and explanation of Christus Victor in the Lutheran confessions of the Book of Concord. The theologians of the Augsburg Confession assembled a Catalogue of Testimonies to show that not only was their theology of the two natures in Christ scriptural, it also was the catholic faith from the apostolic era onward. Wheaton’s Suffering, Not Power serves a similar purpose regarding the relationship between vicarious satisfaction and Christus Victor in the Lutheran confessions. It amounts to a fledgling catalogue of Middle Ages testimonies showing the catholicity of Lutheran Orthodoxy’s doctrine of atonement.

Wheaton is an Evangelical Protestant, not a Lutheran. But he is approaching the matter historically. His approach is not hampered by dogmatic or confessional commitments of his being an Evangelical Protestant. He observes history and lets history speak for itself. His result observed from history, namely that “the reconciliation of God and mankind was not dependent upon the defeat of the enemy powers; rather the reverse,” is compatible with Luther and Lutheran Orthodoxy.

[1] Gustaf Aulén, Christus Victor: An Historical Study of the Three Main Types of the Idea of the Atonement, trans. A. G. Hebert (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc., 1969), 158.

[2] A. G. Herbert, “Translator’s Preface,” Christus Victor, xxi.

[3] Wheaton, Suffering, Not Power, 1, 25, 241.