Ulrich Luz

The Theology of the Gospel of Matthew

Review

Outline

- Citation

- The Author

- Nature of the Work

- Matthew as Story

- The Text Invites Reading as a Narrative

- Author and Sources

- Reading Synchronically

- Structure and Meaning

- Sampling Results of Narratological Reading

- Faith and Works

- Breakdown in Luz’s Approach

- Scripture

- Evaluation

Citation

Luz, Ulrich. The Theology of the Gospel of Matthew. trans. J. Bradford Robinson. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

The Author

Ulrich Luz is a world-renowned theologian. He is regarded highly for his extensive work in the study of the Gospel of Matthew. Besides the book being reviewed here, a selection of his writings on Matthew include:

Matthew 1-7: A Commentary, trans. James E. Crouch, (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2007).

Matthew 8-20: A Commentary, trans. James E. Crouch, (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2001).

Matthew 21-28: A Commentary, trans. James E. Crouch, Fortress (Minneapolis, MN), 2005.

Matthew in History: Interpretation, Influence, and Effects, (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1994).

Studies in Matthew, trans. Rosemary Selle, (Grand Rapids: Wm. B Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2005).

The first three of those are volumes in Hermeneia—A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible.

His significance for Lutherans can be anticipated by how many of these works have been published by Fortress Press. I was introduced to Luz on Matthew by quotations from him by other Lutheran commentators on Matthew.

Nature of the Work

Luz’s other works on Matthew are of other genres: critical and historical commentary, redaction criticism, literary criticism, exegesis, and study of the effects of interpretations of Matthew in world history.

This book is different. The publisher and series editor identified a gap in the body of literature on Matthew. While there are many exegetical, critical, historical, and homiletical commentaries and other studies, they believed there are too few theological texts on Matthew. They prescribed a series of texts to remedy that deficiency. Luz takes up the assignment for Matthew in the series.[1]

Matthew as a Story

From among alternative approaches, Luz chooses a “Matthew’s Story of Jesus” approach like R. A. Edwards and J. D. Kingsbury,[2] as opposed to, for one example, systematic organization by topic. “The Gospel of Matthew is a story of Jesus that can only be understood when one retraces it and tries to grasp what it wished to convey to its intended readers.”[3]

Despite a lot of source, authorship, and text criticism present in Luz’s thinking, his basic idea is expressed in the heading of the first section of his first chapter: “Matthew’s Gospel as a Coherent Book.” He sees coherency in story or narrative. Because of that, he encourages reading it straight through. Doing that lets the text operate as intended; it lets the intended meaning and message come through.

After observing several reasons why people today usually read isolated passages from the Gospels rather than reading through as a narrative, Luz says why this is a mistake.

This is to overlook one very important consideration: all the Gospels, though perhaps least of all Luke’s, have an internal ‘line of tension’ extending from beginning to end. Each has an underlying conflict that arises in the course of the narrative, reaches a climax and arrives ultimately at a resolution. In the English-speaking world this underlying conflict is called the ‘plot’ of a story, though perhaps ‘plan’ might be a better word.[4]

The Text Invites Reading as Narrative

“The Gospel of Matthew invites reading from beginning to end. This is made apparent by many indications in the text itself.”[5] These include:[6]

- Signals — Matters that stand out as unclear or incomplete in excerpt and only become clear or complete by reading onward.

- Prophesies — Here we refer not to prophesies of the Old Testament, but prophesies made in Matthew’s Gospel itself, the understanding of which depends on reading onward to observe more clues of a prophesy being revealed or a fulfilment of a prophesy.

- Key words — Terms like “righteousness,” “judgment,” and “Son of man” that occur with high frequency, but not necessarily evenly distributed, so that where they occur becomes significant.

- Repetition — Intentional repetitions of things like withdrawals by Jesus from the people, formulae like “weeping and grinding of teeth,” and warnings to disciples to be watchful.

- Inclusions — Sections that are bracketed by a particular catchword or motif. On the large scale, the whole Gospel is an inclusion bracketed at both ends by the fundamental Christological motif of “God with us” in Immanuel, 1:23, and “Lo, I am with you always, even to the end of the age, 28:20. Within that grand inclusion, similar internal inclusions occur.

- Cross-references and Flashbacks — E.g., the episode of the grave watchers and their bribery (27:62-66 and 28:11-15) as a reference back or a flashback to Jesus giving the sign of the prophet Jonah (12:4) when the Pharisees were also present. “The final passage in the Gospel of Matthew is like a large terminal railway station in which many lines converge.”[7]

“All of these literary techniques are only recognizable to readers who choose to read the Gospel as a continuous narrative rather than in excerpts and individual pericopes.”[8]

Place in Narrative Approach

Luz is not the only commentator on Matthew to take a narrative approach, of course. But similarities to others who use a narrative approach are not so extensive that one could skip over Luz on the theory that “If you’ve seen one, you’ve seen them all.”

First, as Warren Carter notes, “While identifying this approach with ‘literary criticism’ and generally following the order of the Gospel, Luz employs little from literary studies.”[9] Maybe this book by Luz falls into a category that we could call “narrative criticism.”[10]

Second, Luz’s tracing of the plot does not simply track the studies of Matthew’s plot by others and this book does not engage those others, such as Kingsbury,[11] Matera,[12] Powell,[13] and Carter.[14]

Thus, Luz has his own place in this genre. On reflection, I agree with Carter that Luz represents not a narrative approach generally, but narrative criticism. As will be seen below, his ideas about the sources of Matthew and the role of redaction criticism in the interpretation of Matthew make Luz’s treatment a somewhat different breed of cat.

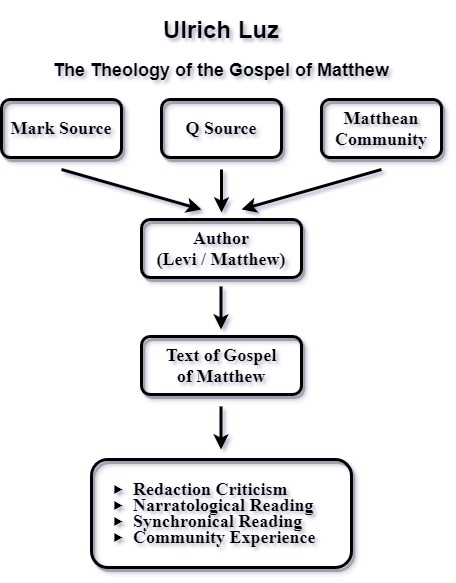

Author and Sources

As in his three-volume commentary, Luz exhibits a redaction-criticism view of the author and sources of the Gospel of Matthew. Immediately, this is a blemish and a disappointment. I have no trouble believing that the author is the Levi Jesus called as one of the Twelve,[15] also called Matthew,[16] and no trouble believing that he was able to write this Gospel because of (a) Jesus’ own promise of the Holy Spirit,[17] (b) Matthew’s time with Jesus, (c) Matthew’s probable language and recordkeeping skills as required for Roman civil service as a tax collector,[18] and (d) his post-ascension work with the Apostles.[19]

Luz holds to Matthew having used a “Mark source” and a “Q source”, but he still credits the author for having his own intention in writing. For example, concerning his use of repetition: “Since Matthew shows himself capable in many other passages of recognizing and unifying duplications it would be wrong to attribute such repetitions to literary ineptitude or mere deference to tradition. . .. [H]is repetitions are deliberate, not proof of literary incompetence.”[20]

I consider Luz’s section headed “Matthew’s Predecessors” to be largely error. It makes Matthew dependent on Mark, posits the logia or sayings of Q, and posits other sources for Matthew’s Gospel. It speaks almost as if Matthew would not have known what to say without those sources.

Similarly, I consider his section headed, “The Matthean Community in Opposition to Judaism” to be largely error. Despite that title, it is more about who he thinks the author was. Luz is not following the early church, tradition, or the conclusions of others such as Gibbs, Lenski, and Morris. The line of thought takes on a sociological bent. It is as if the (speculatively identified) “Matthean community” is influencing what Matthew decides to include or exclude. For example, when he compares what he thinks is Matthew’s source for 15:1-20 in Mark 7:1-23, Jesus rejects ritual law in Mark but not in Matthew, because the Matthean community was keeping ritual law. The tail is wagging the dog, or as we say in Montana, the horse is riding the cowboy.

Sometimes Luz writes as if demands of the “Matthean community” hermeneutic caused Matthew to just make stuff up to fit the narrative. For example, he says of the unholy triple alliance against Jesus of Herod, the high priests and scribes, and all of Jerusalem:

This would have surprised those readers of Matthew’s Gospel who knew the actual story of Herod, for such an unholy alliance contradicts any form of historical probability.[21]

The identity and characteristics of the Matthean community are addressed directly in the section headed, “An Outline History of the Matthean Community.” This becomes the vehicle for him to account for the sources and origin of Matthew’s Gospel:

The discovery of the Gospel of Mark apparently played an important role in the community’s reorientation [from mission to Jews to mission to Gentiles]. I am quite certain that Mark’s Gospel, unlike the Sayings Source, did not represent the community’s own traditions but entered it from the outside. Either it was a book from the Gentile-Christian Syrian communities among whom the Matthean community now lived, or it originated in the west, in Rome. Wherever it came from, it took on significance within the Matthean community. Linking his Gospel within the traditions of his own community, the author of Matthew created a new edition of the Gospel of Mark that answered the questions with which he was now confronted.[22]

The community-as-source implication becomes express on passing from the introductory material to Matthew’s prologue.

The Gospel of Mark opens with the story of the appearance of John the Baptist and the baptism of Jesus. Matthew prefaces this opening with a genealogy (1:2-17) and an infancy narrative (1:18 – 2:23), both of which he presumably took from the oral traditions of his community.[23]

It even infects something as vital as the virgin birth. “Matthew adopts and takes seriously the Christology of his community, which spoke of Jesus as the son of a virgin.”[24]

This aspect of the Matthean community sometimes causes the narratological reading of the text to spiral out of control. For example, after the Sermon on the Mount, Luz invites us to an inclusivist reading of text that passes from narrative about Jesus to being symbolic about ourselves. He literally encourages us to project the text onto our experiences.

Matthew’s readers project this miracle story onto their own experiences. They may have thought of their own lives, of illness, death or material want, or of the experience of their community, perhaps the persecutions they suffered. . . . It is more important that the story provide opportunities for associations from one’s own life than that it prevent such associations. [25]

Reading Synchronically

Luz’s redaction criticism – his ideas about the author and source – could ruin a commentary were it not for Luz’s approach to interpretation: “Simply looking at the signals in the text ‘synchronically’ (i.e., independently of its sources).”[26] Despite who the author might be and despite what sources the author used, reading the text synchronically is the right way to read it, Luz asserts, because the author had to know that it was the only way his first intended audience could read it.

Nor should we let ourselves be misled by the nature of the source material: only today are we aware that Matthew simply prefixed chapters 1 and 2 to his Marcan source. Most of the earliest readers of his Gospel would not have known this.[27]

In addition, Luz does ground his symbolic application of Matthew’s miracle stories in historical fact.

To view miracle stories symbolically, then, does not mean that they did not really happen and must therefore be transported to a symbolic level lest they become meaningless. Just as the spiritual interpretation of the Scripture by the later Church never superseded its literal interpretation, the present-day significance of a miracle story never superseded, for Matthew, the fact that in really did once occur, namely, during Jesus’ lifetime.

Reading synchronically, grounding miracle stories in historical fact, and the narrative approach in general rescue significant parts of Luz’s reading of the text. Despite his errors, Luz comes through with brilliant insights, so that it is no wonder that Gibbs makes use of his work, albeit in a carefully limited way.

Structure and Meaning

Narrative or story has four elements: conflict, characters, plot, and resolution. Of course, Jesus is a major character in the Gospel of Matthew. We are familiar with many of the other characters: disciples, scribes, Pharisees, publicans and sinners, women, John the Baptist, Herod, Pilate, the Sanhedrin, Satan, demons, lepers, and so on.

In Luz there are characters with whom we might not be so familiar: communities. The factor of communities affects Luz as to authorship and sources, as noted above, and then it affects him in his view of the structure and meaning of Matthew’s Gospel. His outline, his discussion of passages, and his upshot for the whole Gospel of Matthew bear distinct marks of a community-centeredness to his plot line.

To be fair, however, both here and in his three-volume commentary, Luz emphasizes a major, if not the major, theme of Matthew: the intervention of God into the plot line with His own divine plan. This is pronounced enough that it accounts for his preference for the word “plan” over “plot” in Matthew.

He lays out the structure in the table of contents like this:

- Prologue (1:1 – 4:22)

- Discourse on the Mount (5 – 7)

- Ministry of the Messiah and his disciples in Israel (8:1 – 11:30)

- Origin of the community of disciples in Israel (12:1 – 16:20)

- Life of the community of disciples (16:21 – 20:24)

- Final reckoning with Israel and the judgment of the community (21:1 – 25:46)

- Passion and Easter (26 – 28)

Note the role of the community of disciples. Note that the final reckoning with Israel is a judgment of the community. The community of disciples originated in the community of Israel, and the line of tension dramatically speaking climaxed with the failure of mission to the Jews, the rejection of Messiah by the community, and a judgment reckoning with the community culminating in passion and Easter. Following Easter, the Matthean community’s direction is turned from mission to the Jews to mission to the Gentiles.

Luz sees the story of Jesus himself going to Galilee of the Gentiles as the foreshadowing of the Matthean community turning in mission toward the Gentiles. This is somewhat forced, however, because Luz says there is no warrant for Matthew saying Galilee is of the Gentiles, and Matthew just supplied that to make the narrative structure work. Luz is at his weakest when he says things like this.

Sampling of Results of Narratological Reading

Beginning immediately upon passing from the introductory material to Matthew’s prologue, Luz’s narrative approach gets important things right that others get wrong.

Luz shows that Matthew’s Gospel is not a biography. Matthew omits so many elements that we ought to be able to expect in any conception of what a biography is.[28] Matthew is a gospel.

Most commentators limit the prologue to chapters 1 and 2. They do this for a variety of reasons, such as the fact that from the end of chapter 2 to 3:1, Matthew leaps over 30 years between the return from Egypt to Nazareth to the appearance of John the Baptist. But from a narrative or story perspective, three decades notwithstanding, “3:1 does not mark a break in the narrative.”[29] Having just said that Jesus would be called a Nazarene, Matthew next says, “About that time,”[30] or “In those days” (NKJV), John the Baptist came preaching. The sameness that warrants “that” time or “those” days is not chronological proximity but narrative prologue. Narratively speaking the appearance of John still is prologue. Once Jesus began to preach, wham!, we have crossed a boundary from prologue to the middle of the story.

Having gotten the boundary of the prologue right narratologically,[31]then the prologue can succeed at serving its purpose: (a) “Jesus’ path in the Prologue foretells his entire story;”[32] (b) the prologue is a key text in Christology; and (c) the prologue inaugurates the action as fulfillment of prophesies.

Besides the explicit references to fulfillment of Old Testament prophesies, the narratological reading sensitizes the reader to experience character, conflict, and plot reminiscences that sometimes parallel and sometimes invert plot, conflict, or characters from Old Testament stories. These reminiscences affect the portrait of Christ a reader gets from the text.

Recall what Luz has said about the narrative device of inclusions, particularly the inclusion formed by “Immanuel, God with us” in the prologue, and “Lo, I am with you always” at the end. This sets up an understanding of everything Jesus says and does in the narration as having an import of Jesus being with his disciples. What He preaches (e.g, the kingdom of heaven is near) and what He does (e.g., cleansing a leper who otherwise would be segregated) are about the presence of God.

When members of the Matthean community read or listened to Jesus’ sayings they heard the way in which God is ‘with them’ in the present. When they listened to what Jesus said, they heard what he is telling them today.[33]

Inside that grand inclusion is another inclusion: The Son who obeys his Father, who fulfills all righteousness. “Jesus, it need hardly be mentioned, does not stand in need of atonement!”[34] Yet he submits to baptism by his lesser, John. This obedience becomes amplified in the wilderness temptation where Jesus demonstrates his sonship not by working miracles and seizing power but by appealing to and obeying God’s Word.

Later this thought will recur in a quite similar manner in the story of the passion. The Son of God is the man who, resisting the temptation of the scribes to save his life, refused to descend from the cross and drinks the cup of suffering that God has offered him.[35]

The same thought recurs in the middle of the gospel. Once Peter acknowledges that Jesus is the Son of God, “Jesus points the disciples to the path of obedience, which is that of suffering (16:21ff). It is precisely here that they encounter failure.”[36]

These concentric narrative inclusions converge into a unity: “God is present precisely by being with his obedient Son, whose path leads to suffering and death.”[37]

This in turn becomes the application of Matthew to the believer. Luz adverts to the tension and disagreements among commentators and theologians about salvation by grace versus salvation by obedience. This issue arises recurringly in the book, at first without Luz sharing his ultimate view, and gradually, like narrative itself, pulling back the curtain a little more each time he treats the issue. In the end, he leaves a heavy emphasis on obedience, a demand of Christ upon disciples made an easy, or at least easier, yoke by the presence of Christ with believers. The path of the Christian’s narrative, like the path of Christ himself, leads to suffering and death, in all of which the Christian, like Christ, must obey, and which the Christian does, like Christ, with the presence of God.

Stories have three parts: a beginning, a middle, and an ending. Early on Matthew signals his penchant for this form, such as when he divides the story of Jesus from Abraham to Joseph into three neat eras of 14 generations each. He continues molding his narrative using narrative structures. “The final result of this . . . is a literary miracle of symmetry, poise, and unity.”[38]

Matthew is so thoroughgoing in employment of narrative forms that even when he comes to lengthy discourse, such as the Sermon on the Mount, the sermon follows narrative structure. The Sermon falls into three sections. The main, center section in turn divides into three sections. Seen this way, the center of the Sermon is the Lord’s Prayer, the “Our Father.” The word Father dominates the central section of the Sermon. Luz uses this to interpret all sorts of things great and small about the Sermon. He even uses it to provide his answer to the question, “Is Matthew the classical exponent of a non-Pauline righteousness of works.”[39] “The entire Sermon on the Mount is a proclamation of the will of God to men and women who are children, and who are permitted to pray to their Father because he is near to them and hears them.”[40] Beginning there, Luz asserts the dramatic tension between the demands and promises of the Sermon. And true to dramatic form, while a resolution is suggested, the plot still is in a phase of rising action. The full interpretation of the Sermon awaits the further development of the Sermon in its third section on the final judgment. The Sermon ends with a forward glance to the final judgment, just as the whole Gospel ends with a forward commission for the Church Militant.

This narrative approach yields a brilliant insight about prayer.

That the core of the Sermon on the Mount is found in prayer – i.e., that the Lord’s Prayer is not located somewhere else in the Bible – is of cardinal importance to Matthew. The imitation of Jesus’ way, then, means action and prayer, daring and prayer, obedience and prayer, suffering and prayer. This ‘and’ is central to Matthew’s cast of thought.[41]

Faith and Works

Whereas for Lutherans, faith clings to the Word alone, against all appearances and experience, the inclusive interpretation that includes the Matthean community in the narrative of the Gospel causes faith to be a mixture of faith and experience. The members of the community believe partly because of their experience of inclusion in the story, and the redaction-critiqued text ofttimes is even the result of the experience of the community. For Lutherans, the word “trial” always means “trial of faith”[42] and faith means faith in the Word. Trial is not just any difficulty or suffering. Trial strips away other supports and leaves the Christian with only the Word.[43] We walk by faith, not by sight.

Luz’s resolution of the tension between the demands and promises in Christ’s discourses is not in concord with Lutheran theology. At the end of the book, Luz tries to have it both ways, for example when he compares Matthew and Paul.[44] In the midst of the book, however, he says, “The promise of salvation is conditioned on human activity. Blessed are those who learn — and those who exert themselves.”[45] “The attainment of grace through obedience — human activity — becomes a significant feature of the community of disciples.”[46]

Perhaps judgement and grace belong in a dialectical relationship. A God who only loves but does not pass judgement would be a forgiveness dispenser who could be manipulated at will. [citing Voltaire] A God who only passes judgement but does not love, first and foremost, would be a monster.

We remain in a quandary. It seems to me that the notion of judgement according to works is a theological impossibility for the God who abides in Jesus of Nazareth and who defined himself in the resurrection. But it may be that we, as human beings, need the idea of judgement because, without it, we would be unable to take God seriously as God. The idea may be an anthropological necessity. Is this the solution to the deep dilemma underlying not only the Gospel of Matthew but the New Testament as a whole?[47]

Although I will not go into it here, the reader of Luz will encounter the results of his reading of Matthew for additional matters such as the conception of the Church,[48] Mission and the Ministry,[49] and Sacraments.[50]

Breakdown in Luz’s Approach

The narratological reading is the strongest part of Luz’s book. That is what produces his best theological results. The principle of synchronical reading also helps the book.

Unfortunately, however, two additional principles undermine both the narratological reading and the synchronical reading: (1) redaction criticism, and (2) interpretation of the text as having been written after-the-fact of Matthean community experience to conform the text to that experience. These two principles in stereo increasingly dominate the commentary. As one proceeds through the book, increasingly, the principle of synchronical reading is only a bandage on the wound of Luz’s source and authorship premises. He applies the bandage over too small an area, the wound being much larger. While the synchronical reading helps, too often it seems to have gotten little more than lip service, and then the remaining two principles of interpretation dominate.

For example, the inclusion of the Matthean community in the narrative of Jesus means that the arc of their plot-life imitates his. He started out with rejection by the leaders but a favorable reception from the people.[51] Suddenly near the end, the people also turn on him and he begins including the people in his prophesies and judgments along with the leaders.[52] Similarly, the Matthean community started out with opposition from the leaders but favor among the people. Suddenly, however, the people turn on them and reject their mission. This has happened just lately before the author of the Gospel of Matthew writes, so in the community’s experience, it has a suddenness like the suddenness of the turn against Jesus near the end of his earthly life. This application of narratological inclusion swal-lows the Matthean-community-experience source of the text and gives it prominence in the redaction criticism. Is God speaking to us by inspiration of the Apostle, or is the author of Matthew giving the community an echo chamber?

Let us look at examples of the impact of this on theology.

Luz undermines Jesus as Prophet. The author is taken to be writing after the destruction of the temple. The experience of the Matthean community from its destruction becomes an exogenous injection into the prophesy of Jesus about its destruction. Jesus is not really prophesying because He did not say this ahead of the event. Rather, the community is speaking through the author about its experience of the destruction.

Luz undermines Matthew concerning Jesus’ conflict with the Pharisees.

Being antitypes, the Pharisees and scribes must be denigrated. Whether all Pharisees or only a few really were as Matthew describes them does not interest the evangelist in the slightest. What he needs are negative stereotypes so that his community can stand out to advantage. Today we know that the Pharisees were thoroughly capable of viewing themselves with a critical eye, and that there are points of agreement between Matthew’s critique and Pharisaic self-criticism. Matthew’s critique, however, is wholesale and therefore unjust. … It contains all the features associated with prejudice. Prejudice enables a person readily to find a cognitive orientation in times of difficulty. Having been expelled from Pharisaic Judaism, the Matthean community needed to do just that. It had to define what it was not. But Matthew’s discourse of woe is far removed from fairness or righteousness – and certainly very remote from the commandment to love one’s enemy.[53]

He goes on, but you get the idea.

Luz undermines Matthew concerning the rejection of Jesus by the high priests, elders, and crowd during his trial before Pilate.

The whole scene is his own creation – it was lacking in his Marcan source. The truth of this gruesome scene is, for Matthew, not to be found in history. Within his own lifetime he had experienced the repudiation of Jesus by the entire people of his country, Israel. It is this experience that he has inserted into his Jesus story, explaining its meaning for that people. Matthew 27:25 is a case of staged dogmatics.[54]

Scripture

By now you might sense something amiss in Luz’s doctrine of Scripture. He wants to “prevent us from succumbing to mindless Biblicism.”[55] The trouble is, to avoid mindlessness, Luz exercises a prerogative to stand magisterially over Scripture. This is simply going from one ditch to the other and not keeping in the road.

Evaluation

Whether I recommend that a person read Luz’s The Theology of the Gospel of Matthew depends on who the person is, the purpose of the person reading it, and how many other commentaries on Matthew the person has read already or is planning to read.

For theologians, pastors, and advanced lay people I recommend it for the following reasons:

- I agree with Luz’s basic point about narratological reading of Matthew.

- Despite the redaction criticism flaws, Luz provides worthwhile insights resulting from his reading the text synchronically, and this category of readers is not likely to be harmed by the errors since they are able to read the work critically.

- Luz holds a significant place in the body of literature about how today’s world reads Matthew. Even if one does not agree with Luz, reading him provides information about the views of the world around us.

- Reading this work is the fastest and easiest way to sample Luz because it is one of his shortest and least technical books. The body is only 159 pages and J. Bradford Robinson has translated it fluent into English.

- The book succeeds at getting its reader to think, what is Matthew trying to do and how is Matthew trying to do it. These questions engage the reader in the question, what message, what doctrine, what faith is God giving me in Matthew.

For other lay people, however, I would drop Luz’s The Theology of the Gospel of Matthew from my bibliography. For most lay people, time would be invested better elsewhere. Many lay people might not be equipped to read Luz critically and discern the lines between his valuable insights and his errors.

Perhaps the greatest tragedy of Luz’s work is this: Having rightly identified the story of Jesus as being about Immanuel, God with us, and staking all of Matthew’s continuing vitality for today on God’s continuing presence with us,[56] he never gains from Matthew where or in what God has promised to be present. There is no whiff of Real Presence in the Sacrament, no whiff of the presence of Christ in Baptism, and nothing overtly or expressly said about the presence of God in the preaching and hearing of the Word.

Luther preaches:

“He took them up in His arms, laid His hands on them, and blessed them.” Mark 10:16 [Matthew 19:13-15] He is just as present in Baptism now as He was then.”[57]

Where Baptism is, there heaven is certainly open and the entire Trinity present, sanctifying and blessing through Himself the one being baptized.[58]

But come to this sign which God has established, where He preaches the Gospel to us and strengthens us with the bread on the altar and with Baptism. And the Lord Christ will say, “You will see Me present bodily in My preaching, baptizing, and absolving, and distributing the Supper.”[59]

[1] Editor’s Preface in Ulrich Luz, The Theology of the Gospel of Matthew. trans. J. Bradford Robinson. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995, ix-x.

[2] Luz, xi.

[3] Luz, xi.

[4] Luz, 1-2.

[5] Luz, 2.

[6] Luz, 2-5.

[7] Luz, 5.

[8] Luz, 5.

[9] Warren Carter, “Review of The Theology of the Gospel of Matthew,” Journal of Biblical Literature 16(1) (1997): 145-46.

[10] Mark Allan Powell, “The Plot and Subplots of Matthew’s Gospel,” New Testament Studies 38(2) (1992): 187-204.

[11] Jack Dean Kingsbury, “The Plot of Matthew’s Story,” Interpretation 46 (October 1992), 347-356.

[12] Frank J. Matera, “The Plot of Matthew’s Gospel,” The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 49(2) (1987): 233-253.

[13] Mark Allan Powell, “The Plot and Subplots of Matthew’s Gospel, New Testament Studies 38(2) 1992: 187-204.

[14] Warren Carter, “Kernels and Narrative Blocks: The Structure of Matthew’s Gospel,” The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 54(3) (1992): 463-481.

[15] Mark 2:14-17; Luke 5:27-32.

[16] Matthew 9:9-13, 10:1-4; Mark 3:13-19; Luke 6:12-16.

[17] John 14:25-26.

[18] G. Jerome Albrecht and Michael J. Albrecht. People’s Bible Commentary: Matthew, rev. ed. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2005, 4; R. C. H. Lenski, The Interpretation of St. Matthew’s Gospel. Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House, 1943), 362.

[19] Acts 1:12-14.

[20] Luz, 4.

[21] Luz, 27.

[22] Luz, 19.

[23] Luz, 22.

[24] Luz, 30.

[25] Luz, 67.

[26] Luz, 23.

[27] Luz, 22.

[28] Luz, 23.

[29] Luz, 22.

[30] Luz, 22.

[31] Or nearly so. Luz is a bit off. Gibbs is more correct.

[32] Luz, 29.

[33] Luz, 33.

[34] Luz, 35.

[35] Luz, 36.

[36] Luz, 36-37.

[37] Luz, 37.

[38] Luz 48.

[39] Luz, 47.

[40] Luz, 49.

[41] Luz, 158.

[42] Walther von Loewenich, Luther’s Theology of the Cross, trans. Herbert J. A. Bouman (Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House, 1976), 136-139.

[43] Christ is our Pioneer in this. When He heard the Word of God in his Baptism saying, “You are my beloved Son,” immediately the Spirit of God drove him into the wilderness to be tempted by the Devil, who said, “If you are the Son.” “You are my Son” versus “If you are the Son.”

[44] See the section headed “Matthew and Paul” in the final chapter, 146-153.

[45] Luz, 96.

[46] Luz, 96.

[47] Luz, 132.

[48] E.g., Luz, 90, 91-92, 97.

[49] E.g., Luz, 75-80.

[50] Luz, 157.

[51] Luz, 116.

[52] Luz, 123.

[53] Luz, 123-124.

[54] Luz, 135.

[55] Luz, 153.

[56] Luz, 159.

[57] Martin Luther, Martin Luther on Holy Baptism: Sermons to the People (1525-30), trans. Benjamin G. Mayes (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2018), 8.

[58] Ibid., 35.

[59] Ibid., 66.